Epstein Didn’t Hide Among the Elite. He Belonged to Them

- FD Correspondent

- Jan 3

- 5 min read

The Jeffrey Epstein scandal endures not because of unanswered questions, but because of an answered one we refuse to accept: the elite are not accountable to the same moral or legal order as everyone else. The Epstein files—flight logs, photographs, depositions, calendars, settlements—do not merely document a sex-trafficking network. They map a system of elite impunity, sustained by familiarity, money, and institutional deference.

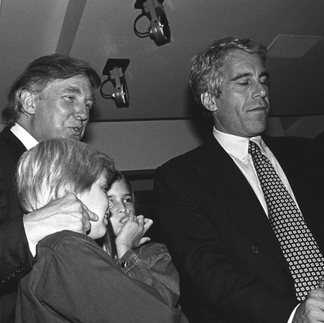

Epstein was not a gatecrasher. He was a host. He socialised with Bill Clinton, flew with him on private jets, and moved comfortably in the orbit of presidential power. He partied with Donald Trump, was photographed with him, and frequented Mar-a-Lago. He enjoyed extraordinary access to Prince Andrew, a relationship so close it ultimately forced the British monarchy into a costly settlement after Virginia Giuffre accused Andrew of sexual assault. Andrew denied the allegation, but the institution paid to contain the damage.

This is not a coincidence. It is how power recognises its own. Epstein’s continued relevance after his 2008 conviction—when he should have been untouchable—was the real scandal. Instead of exclusion, he was rehabilitated. Leslie Wexner, one of America’s most powerful billionaires, entrusted Epstein with sweeping control over his wealth. Leon Black, the private-equity baron, paid Epstein millions after his conviction. Bill Gates met Epstein repeatedly in the years that followed. Gates would later describe these meetings as a “mistake,” a word that trivialises what was in fact a conscious suspension of moral judgement.

Epstein’s network extended seamlessly across borders. Ehud Barak, former Israeli prime minister, was photographed entering Epstein’s Manhattan mansion years after the conviction. Jean-Luc Brunel, a modelling agent deeply enmeshed in Epstein’s operation, was charged in France and later died in prison—one of the few men in this ecosystem to face sustained legal pursuit. Alan Dershowitz, Epstein’s lawyer and one of the most powerful legal figures in the United States, moved from defender to accused, denied wrongdoing, and emerged professionally intact.

What unites these names is not proven criminal guilt. It is something more structurally revealing: proximity without consequence. In any functioning moral order, association with a convicted sexual predator would be disqualifying. In elite culture, it is manageable. Epstein remained useful. He had money, access, and leverage. He could fund research, broker introductions, flatter egos, and offer discretion. Above all, he understood an unspoken rule of elite life: nothing matters unless it becomes unavoidable.

Institutions helped ensure it did not. Prosecutors engineered a non-prosecution agreement so aberrant that a federal judge later ruled it violated victims’ rights. The deal shielded Epstein’s unnamed co-conspirators and excluded victims entirely. Financial institutions continued to move Epstein’s money despite internal red flags. Universities accepted his donations. Foundations normalised his presence. Media organisations hesitated under legal and reputational pressure. Law enforcement treated him as a liability to be contained, not a crime to be dismantled.

This was not conspiracy. It was aligned self-interest. Each institution acted rationally within its own incentives. Each deferred risk upward. No one wanted to be the actor who collapsed the room. The result was a distributed system of protection in which responsibility was fragmented and accountability endlessly postponed.

The point is not that everyone who encountered Epstein committed a crime. The point is that no one paid a meaningful price for staying close to him—even after he was a convicted sex offender. In elite culture, proximity to power functions as insulation, not exposure.

After 2008, Epstein did not disappear. He recalibrated. His social world narrowed but hardened. He became quieter, more selective, more protected. Universities still took his money. Scientists still entertained his patronage. Banks still serviced his accounts. Prosecutors still deferred. When scrutiny intensified, it stalled before it reached the network.

This is what institutional protection looks like in practice: not a single cover-up, but a series of predictable decisions in which the cost of exposure outweighed the cost of silence.

Even now, as documents are unsealed and names re-enter public circulation, the response remains telling. Statements are issued. Timelines are clarified. Distance is emphasised. But the central question is never addressed: why was Epstein welcome at all? Why was a known abuser still fundable, useful, and socially admissible?

The Epstein files reveal that elite corruption rarely announces itself through indictments alone. It operates through normalisation—through dinners that “meant nothing,” flights that were “just transport,” meetings framed as “philanthropy,” and silence justified as prudence.

Epstein did not corrupt the elite. He exposed its operating logic. He showed how accountability thins as wealth rises, how institutions designed to protect the vulnerable instead prioritise stability and reputation, and how exposure itself has become survivable for those at the top. His death closed one legal case, but it left intact the system that made him possible.

That is why the names matter. Not because they establish universal guilt, but because they reveal a universal rule: at the highest levels of power, association is rarely accidental—and almost never punished. Until proximity to abuse becomes disqualifying rather than survivable, Epstein will not remain an exception. He will remain a template.

And the elite will remain what the files show them to be: interconnected, insulated, and protected—by design.

Epstein and the Architecture of Elite Protection

Who Appears in the Record |

Jeffrey Epstein maintained documented associations with senior political, financial, and cultural figures. These include Bill Clinton (named in private jet flight logs), Donald Trump (photographed socially; Epstein visited Mar-a-Lago), and Prince Andrew, who denied sexual assault allegations by Virginia Giuffre but settled a civil case in 2022 and withdrew from royal duties. |

Epstein also maintained close ties with powerful financiers and global elites: Leslie Wexner, who granted him sweeping financial authority; Leon Black, who paid Epstein millions after his 2008 conviction and later resigned from Apollo; Bill Gates, who met Epstein repeatedly post-conviction and later called it a “mistake”; and Ehud Barak, former Israeli prime minister, photographed entering Epstein’s New York residence years after the conviction. |

Jean-Luc Brunel, a modelling agent linked to Epstein, was charged with rape and trafficking in France and died in prison in 2022. Alan Dershowitz, Epstein’s lawyer, denied accusations by Giuffre and later settled defamation litigation. |

How protection operated |

In 2008, US federal prosecutors in Florida signed a secret non-prosecution agreement allowing Epstein a lenient plea deal, granting immunity to unnamed co-conspirators and excluding victims—later ruled a violation of victims’ rights. |

From 2010–2017, Epstein resumed elite access, donated to universities, and maintained financial services despite internal compliance warnings at banks. |

In 2019, Epstein was arrested on federal sex-trafficking charges and died in custody weeks later amid jail protocol failures. Subsequent years saw settlements and regulatory fines, but no senior institutional figures faced criminal prosecution. |

The Epstein files reveal a system in which elite proximity carried no penalty, institutions prioritised risk management over accountability, and exposure proved survivable for those at the top. |

.png)

Comments