Small Films Bypass Blockbusters’ Hype by Word of Mouth

- Abhishek Srivastava

- Dec 1, 2025

- 4 min read

The crisis around Agra did not unfold on red carpets or television debates. It played out quietly, at booking counters that would not open and in theatre schedules that kept pushing the film out of sight. As Kanu Behl’s film neared release, it became clear that the problem was not a lack of audience interest but a lack of access. Screens were denied. Shows were placed at poor hours.

Multiplexes cited “programming issues” that, more often than not, worked in favour of the biggest release of the week. In response, forty independent filmmakers came together to sign a declaration demanding fair theatrical space for Agra. Even that did not immediately change things. What finally made a difference was the audience. Festival viewers began sharing messages. Critics urged people to book quickly. Show timings travelled across WhatsApp groups. One late-night show sold out. And that, quietly, changed the conversation. The film did not enter theatres through marketing. It entered through insistence.

As the situation worsened, Behl took to social media with an unusually direct appeal. On his X account, he wrote, “Update on Agra, the film: We’re being denied shows because of the so-called ‘big blockbusters’ and because small films ‘don’t fit into’ multiplex chain programming.”. He followed this with another message that carried a sharper warning: “Spread the word. Or this will just go on and on. And the space for anything else other than mindless ‘infantilised cinema’ will disappear.” These were not publicity lines. They sounded more like a plea for survival. What followed showed how word-of-mouth now works as a parallel system of distribution. Those who had already seen the film urged others to book at once. Messages spread faster than any advertisement. Cinemas extended shows not because of advance buzz, but because delayed screenings suddenly began to fill.

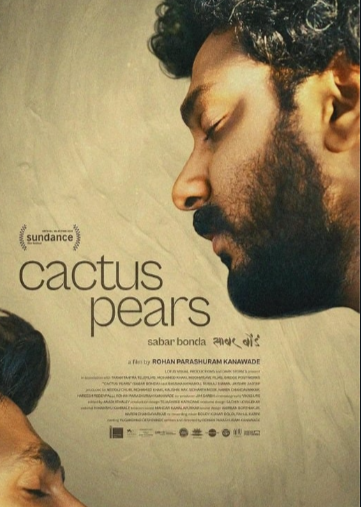

A similar journey was seen with Sabar Bonda, a film that found its audience without loud promotion or heavy media presence. Its visibility grew through small moments: a crowded college screening, a late-night tweet saying, “this deserves to be seen in a theatre,” a quiet recommendation from one viewer to another.

Here, word-of-mouth did not behave like a wave. It moved slowly, built on trust. Someone watched the film and felt the need to pass it on. Time, however, was always the enemy. These films are rarely given more than a few days to prove themselves. Each recommendation carried urgency — go now, before it disappears.

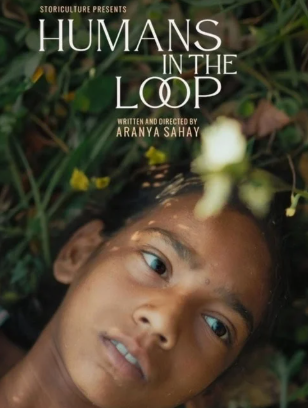

Humans in the Loop offers another example of how audiences can be built without traditional publicity. With a subject rooted in invisible digital labour, the film first found viewers through professional circles. Tech workers shared it with colleagues. Teachers introduced it to their students.

Documentary lovers brought friends to nearly empty halls and watched those halls slowly begin to fill. The film did not grow through spectacle. It grew through recognition. People saw their own working lives reflected on screen. Once that connection was made, the desire to speak about it followed naturally. This was not hype. It was closer to witness. Repeated often enough, that witness began to sell tickets.

The contrast becomes sharper in the case of All We Imagine as Light. Payal Kapadia’s film returned from Cannes with a historic win, placing Indian independent cinema in the international spotlight. Even then, its release in India was uncertain. Kapadia later said, “I was afraid nobody would distribute my film in India… Independent films rarely get theatre distribution — most end up on OTT platforms.” (Source: Cinema Express). It was eventually actor-producer Rana Daggubati who helped secure limited PVR screens. But even after that, the film’s fate rested with viewers. Early audiences urged others not to delay. Social media posts read less like reviews and more like appeals. Shows filled not because of a publicity push, but because people felt a quiet urgency to bring others in.

What makes this system especially hard on small films is that word-of-mouth needs time — the one thing they are rarely given. The Manoj Bajpayee starrer Jugnuma, a slow and meditative film with no interest in conventional storytelling beats, opened on very few screens. Its audience grew one show at a time. A weekday afternoon screening with ten people was followed by a packed weekend late-night show after those ten returned with friends. Film clubs began holding discussions. Photographs of full halls started circulating online as proof that the film deserved to stay. There was no sudden box-office jump. But there was continuity. And today, continuity itself is a form of resistance.

At the heart of all these stories is the same imbalance. These films are not rejected by audiences; they are blocked before audiences can even reach them. Multiplex economics favour scale, stars, and opening-week numbers. Small films are put on silent trial from day one: succeed immediately or make room for the next release. But serious cinema often grows slowly. It needs discovery, not instant deployment. By denying it time, the system forces independent films into competitions they were never built for. Word-of-mouth becomes their only defence and their only weapon — tiring, imperfect, but often the only thing that works.

And yet, small victories continue. Agra survived because viewers refused to let it vanish. Sabar Bonda travelled through personal recommendation. Humans in the Loop moved through communities. Jugnuma stayed alive because people kept returning with others. Kapadia’s Cannes-winning film finally found its Indian audience through steady personal advocacy. These are not victories shaped by marketing strategy. They are stories of persistence. Together, they reveal a parallel cinema economy built on trust rather than advertising budgets. In today’s independent Indian cinema, word-of-mouth is no longer just support for a film. It has become its marketing, its distribution, and often, its only chance at survival.

.png)

Comments