Gujarat's Legacy on Water Conservation

- Teja Lele

- Aug 2, 2025

- 4 min read

Updated: Aug 2, 2025

In Gujarat, where summer heat often shimmers into mirage, a quiet architectural legacy lies below the earth’s surface–stepwells, or vavs as they are called locally. They are subterranean structures that once ensured survival in arid landscapes. Built centuries ago, they are not merely wells but masterpieces of engineering and design—part utilitarian water reservoirs, part places of worship, and part social gathering spaces.

With their cool, labyrinthine depths and intricately carved walls, these stepwells remind us that water was once revered as sacred, especially in the harshest of climates. Gujarat’s semi-arid terrain, coupled with a merciless summer sun, meant that water could be both abundant during monsoons and alarmingly scarce during droughts. Stepwells emerged as an ingenious response to this challenge between 6th and 11th centuries, reaching their peak during the Solanki dynasty in the 11th century. They were constructed by royals, wealthy merchants, and local communities, not only as functional water reservoirs but also as symbols of power, piety, and civic responsibility.

“Architecturally, stepwells are remarkable for their depth and precision. They are often multi-storied structures that descend several stories underground, with a series of steps leading down to the water level, which fluctuates with the seasons,” says Vadodara-based architect Sonali Desai.

The walls and pillars are decorated with carvings depicting gods, goddesses, dancers, and mythological scenes. “Many stepwells were aligned with temples, turning the act of fetching water into a spiritual ritual. The temperature inside the stepwells remains significantly cooler than outside, making them early examples of climate-responsive architecture,” Desai says.

Beyond their architectural grandeur, stepwells were vital community hubs. Women would gather here to collect water, gossip, and rest in the cool shade, while travellers and traders found them to be places of refuge on dusty caravan routes. For rulers, building a stepwell was an act of charity and a demonstration of wealth—ensuring that even during lean years, people had access to water.

Today, many stepwells lie forgotten, filled with debris or fallen into ruin, overshadowed by the rise of modern plumbing. Yet, a revival is underway. Conservationists and architects are now studying these ancient wells not only as cultural artifacts but as functional blueprints for water management in the 21st century. Gujarat’s most celebrated stepwells—Rani ki Vav, Adalaj ni Vav, Bai Harir ni Vav, Modhera Vav, and the Helical Stepwell of Champaner—offer profound lessons in both heritage and sustainability.

Rani ki Vav

Declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2014, Rani ki Vav in Patan is arguably the queen of all stepwells, both literally and figuratively. Built in the 11th century by Queen Udayamati to honour her late husband, King Bhima I of the Solanki dynasty, this grand stepwell stands as both a sacred shrine and a feat of engineering. Spanning seven levels and stretching over 64 meters in length, its walls are adorned with more than 1,500 intricate sculptures. These carvings depict deities from Hindu mythology, most prominently Vishnu in his various incarnations, making the descent into the well feel like a spiritual journey.

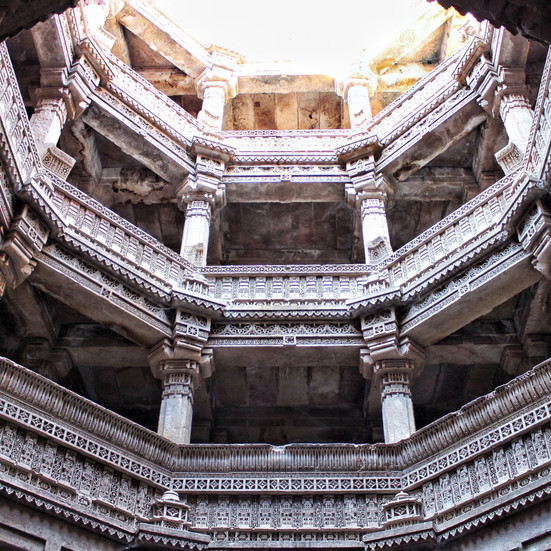

Adalaj ni Vav

Located just outside Ahmedabad, the beautiful Adalaj ni Vav was built in 1498 by Queen Rudadevi. The structure was completed under the patronage of Muslim ruler Mohammed Begda, giving it a unique blend of Hindu and Islamic design motifs. Adalaj is famous for its octagonal entrance, elaborate floral and geometric patterns, and pillared pavilions that descend five levels deep. The well’s design allows for light and air to filter through its corridors, creating an oasis of coolness even on the hottest days. Historically, it was a social and cultural hub where villagers gathered not only for water but also for festivities and prayer. It stands as a reminder that water management in the past was inseparable from community life and cultural exchange.

Bai Harir ni Vav

In the heart of Ahmedabad, Bai Harir ni Vav was commissioned in the late 15th century by Bai Harir Sultani, a noblewoman of the Sultanate era. Unlike the ornate carvings of Rani ki Vav, the beauty of this stepwell (also known as Dada Harir ni Vav) lies in its understated elegance, with sandstone columns and geometric patterns creating a rhythmic descent into the earth. The structure’s spiral staircases and platforms once offered resting spots for travellers, while the well itself captured rainwater for both drinking and irrigation. Its design offers valuable insight into how even smaller-scale stepwells contributed to urban resilience during times of drought.

Modhera Vav

Located near the Sun Temple of Modhera, this stepwell is an extension of a larger spiritual complex built by the Solanki rulers in the 11th century. Known locally as the Surya Kund, the Modhera stepwell is a geometric masterpiece, with perfectly symmetrical steps and shrines dedicated to various deities carved into its walls. It served both as a water tank and as a ceremonial site where devotees purified themselves before entering the Sun Temple. The Modhera Vav is particularly notable for its orientation, which aligns with solar patterns, reflecting the deep connection between cosmic rhythms and water management in ancient Gujarat.

Champaner Helical Stepwell

Unlike the grand, ornate stepwells of Patan or Adalaj, the Helical Stepwell at Champaner-Pavagadh Archaeological Park stands out for its simplicity and innovation. Built in the 16th century, it features a unique spiral staircase that winds around the well shaft, creating a helical descent. This compact design made it easier to fetch water as levels fluctuated throughout the year. Though devoid of intricate carvings, its practicality is its greatest strength, reflecting a utilitarian approach to water conservation. The well’s spiral structure also minimizes surface evaporation, a feature particularly relevant in today’s water-stressed regions.

A Legacy for the Future

The stepwells of Gujarat aren’t just architectural relics; they are living lessons in how past societies lived in harmony with their environment. In an era of groundwater depletion and climate uncertainty, these structures provide a blueprint for sustainable water harvesting and community-focused design.

.png)

Comments