BBC Documentary Papers Over the Real Moosewala

- Charu Soni

- Jul 1, 2025

- 5 min read

“There was no mystery about who killed Moose Wala. The mystery is about why?” states journalist Ishleen Kaur at the very beginning of the two-part BBC documentary The Killing Call that has since its YouTube release on 11 June 2025 garnered 1.2 million views, and a mixed response from Indian viewers.

The documentary which was initially slated for a public theatre release in Mumbai was instead uploaded on YouTube on the day of hip-hop singer Sidhu Moose Wala’s birthday. Sidhu’s family, meanwhile, had filed an injunction in the Mansa court, Punjab, seeking a stay on the documentary screening in Maharashtra.

The BBC instead has stated that its aim is to shed light on the broader criminal networks behind Moose Wala’s murder and provide global audiences with the insights into organised crime in India.

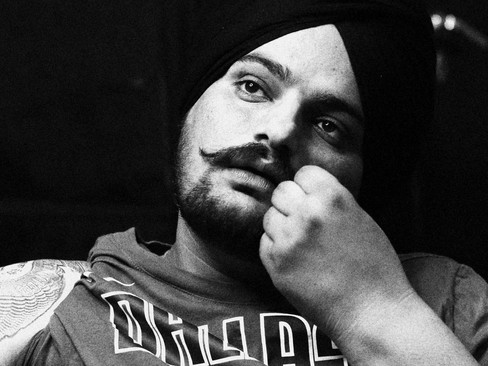

The two-part documentary recreates the sudden rise of Moose Wala as an international hip-hop artiste and then cuts to the events surrounding the singer’s brutal daylight murder caught on CCTV, exploring alleged involvement of gang rivalries and the wider criminal ecosystem connected to the killing.

It matches the police claim that the killing was a result of a gang war. An extortion bid turned into an unfortunate revenge murder. Some 30 people were arrested in the case by the Delhi Police. The murder is still to be solved. But the BBC documentary expertly masks all this, including the complex and turbulent political history of the State, to focus on the theme of gang wars. A gang war that perplexingly embeds Moose Wala in its web.

The crux of the BBC documentary is its reliance on allegedly 6 hours of collected voice notes exchanged with one of the gang leaders, Goldy Brar who declares that “We had no option but to kill him. He had to face the consequences of his actions. It was either him or us. As simple as that.” Brar spoke to the BBC from an undisclosed location outside India.

The stage is thus set for entrapment of the singer who sang about “the pind” (village) especially the Mansa region of Punjab just as 2Pac (Tupac Shakur) sang about “the hood” or Harlem in New York.

To understand the BBC narrative and the life and times of Punjab’s cult idol, one has to take a step back and reprise the social milieu that produces the circumstances in which the crime unfolded.

Without getting into the Punjab quagmire of gang wars, political rivalries, and who is who in police files and who makes headlines in newspapers what is important to keep in mind is the social inequities, the agrarian distress and the farmers’ movement that holds the invisibilised political centre stage for the masses.

History is witness to such moments, moments in which what is made invisible, shines brighter when it burns through the miasma, before it is quickly snuffed.

Sidhu Moose Wala was born Shubh Deep Singh Sidhu in 1993 in village Moosa, district Mansa. In 2016 he graduated as an electrical engineer and moved to Canada for further studies. Soon he found himself in Brampton, Ontario where he dived into the world of rap and hip-hop, releasing his debut track, G Wagon. His collaboration with Big Byrd on the instant hit So High set the stage for his foray into Gangsta Rap.

Gangsta Rap is a genre of music that requires a crafting of an image, in which Shubh Deep chose to embrace a “Thug Life” persona. He named this persona Sidhu Moose Wala -- a cultural idiom through which he could express and challenge societal norms. The playground for his songs, was not Canada, but his village backyard, to which he quickly returned.

This in itself set him apart from many other successful urban Panjabi rappers and hip-hop singers who were more at home with international audiences, than the gritty and hopeless landscape of the village bumpkin.

In the documentary, these nuances are erased. The singer is divorced from his social milieu and placed instead in the realm of financial mismanagement of his net worth (which incidentally are way below an average net worth of a successful Punjabi entrepreneur), extortion calls and some crime story about revenge and gang wars. Visually, this is underlined by presenting footage of Moose Wala moving in SUV cavalcades, juxtaposed with screenshots of him holding AK 47 in his music videos and so on.

There are, of course, passing references to his entry into the political arena as a Congress candidate and a mention of his support of the farmers’ movement. These, however, are not germane to the narrative set for the documentary. The question why he was killed, posed by Ishleen Kaur at the beginning of the documentary, is answered by Goldy Brar, a fugitive small-time criminal, at the end of the documentary. It is a mechanism of storytelling that craftily conceals critical questions and foregrounds hearsay.

And while we may never know on whose instructions the singer was killed, the legacy of his songs, the rhetorical strategies Moose Wala deployed to question hegemonic injustice and encourage social change are a testament to the larger existential questions he posed.

Mansa district, the playground of Moose Wala the prophetic singer and a rebellious truth teller, is one of the epicentres of agrarian crisis hurt both by environmental depredations of the Green Revolution, sub-divisions of land holdings and the neo-liberal reforms in the agricultural sector.

It is also a region that has a history of peasant and agricultural labour union movements. Early on, much before Moose Wala basked in his first hit, he wrote the song Cadillac in which he asserted this umbilical connection, “Sweetheart I come from the village where descendants of Khabi Khan live/ families of fearless live…” The term Khabi Khan is a shorthand for leftist leaders of the region, in other words, people’s revolutionaries.

His later songs, written while he lived in his village, songs like 295 and SYL stage a cultural confrontation with both the hegemonic superstructure as well as the smaller hegemonic groups. They are far more provocative than the 4 FIRs lodged against him for promoting violence, gun culture and vulgarity in his songs.

The song SYL (on Sutlej-Yamuna Link) harks back to the undivided post-Partition Punjab, before it was carved into Haryana, Punjab and Himachal Pradesh. “Return our ancestors and family to us,” he sings in it. In the song 295 he questions the Colonial era law that criminalises religious disagreements. A law that was born of British prejudice. They saw Indians presumptively as “irrational”, “hot headed”, “disloyal” and “seditious”. A law that continues to hold its sway in the country.

But such reading would be difficult to present for a worldwide service broadcaster that faced heat from the establishment for its documentary The Modi Question. Some amends must be made. And a crime documentary made by an obscure Asian music lover and DJ turntablist as a producer, Bobby Friction aka Paramdeep Singh Sehdev, makes for a sumptuous offering.

For the establishment Moose Wala’s death presented a Catch 22 situation. No one expected the surge of people that arrived for his funeral. Punjab has no shortage of martyrs. Creating one more would add to the headache. The resistance needs to be co-opted as part of overarching universal hegemonic philosophy. What could be more palatable than a crime story about a pop star? Singers have been a target of extortion killing before, adding one more to the list is the fastest way to normalise sudden death.

.png)

Comments